A Responsibility to Listen? Policy Makers, Research and 'Impact'

Professor Robert MacDonald

HudCRES

Academics may have a responsibility to make research ‘relevant’ & ‘accessible’ – but should, then, policy-makers and influencers have a responsibility to listen? A note on, and examples of, how critical social research gets side-lined.

It has become almost unquestioned that academics should strive for their research to have influence and effect on ‘the real world’. Not least this is because the real politick and funding regimes of UK research make it difficult to resist this insistence on a public value and pay-off from academic research.

Over the past decade or so, the funding of research – especially by quasi-governmental bodies such as the UK Research Councils and the Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE) – has become tightly tied to the claimed or potential impact of that research on the world 'out there'. Research should be about influencing society, economy and culture rather than just producing abstract knowledge or 'blue skies research'. No 'pathways to impact statement'? No research council grant - no matter how theoretically significant or methodologically robust the study. The seven-yearly Research Excellence Framework (REF) – which distributes multi-millions of pounds to academic departments based on assessment of the quality of their research – will, in 2021, carve out an even greater slice of the funding pie for research that can prove that is has 'made a difference'. Because there are big bucks here, a veritable 'impact industry' of consultants, think tanks, PR firms, funding schemes, new software programmes, 'impact managers', and specialist impact case-study authors, has become embedded in the academy.

This all may - or may not - be a 'good thing'

Some have welcomed the impact agenda as aiding the very long-standing imperatives towards social justice that can be found in much critical social science research ('we want to change the world, don't we?'). Others are wary of research priorities becoming too closely set by the narrow or short-term needs of business or government ('we shouldn't be the paid lackeys of business and government'). And some reject outright the utilitarianism they see in 'the impact agenda' ('what of knowledge for knowledge's sake?') or its narrow, short-term conceptualisation of 'impact' ('Einstein wouldn’t have been funded').

I have conjured with these questions elsewhere - in a recent blog post and journal article. After a slow start, there is now a growing body of critical academic literature on research impact (see for instance the important debate that has been between the distinguished social geographers, Rachel Pain and colleagues and Tom Slater, and in respect of education research, the arguments of Helen Colley, previously of HUDCRES).

The rights and wrongs of impact is not, however, the focus of this post

Rather, I raise the question here of the responsibilities of those with some power to effect change to actually use the research we produce.

The relationship between academic research and public policy is, of course, a complex one. A straightforward relationship between research evidence and policy formation is rarely obvious - even with governments that profess an interest in 'what works' (see Monaghan, 2011). Nevertheless, academics are regularly instructed to undertake research with 'stakeholders', to 'co-produce' with outside partners, to avoid jargon and write in 'lay language', to include those we seek to influence in the research process, to present evidence to government select committees, to publish findings in formats and media which are 'user-friendly' and accessible to different audiences, to get trained in dissemination via social media, to improve our radio or TV interview skills so as better to get our message across, to reduce complex theories and complicated findings to bullet-points and soundbites, to 'tweet' and to 'blog' even!

But what if we do all that and the research still gets ignored, side-lined or forgotten?

With colleagues I have undertaken detailed, qualitative, longitudinal and long-term research with young people growing up in some of the most disadvantaged and deprived parts of the UK (in Teesside, North East England). The Teesside Studies of Youth Transitions and Social Exclusion have been referred to as 'the most intensive example of youth transitions research in the UK' (Gunter and Watt, 2009: 516). The research spans several decades now. This article from 2005 is an example. The young people are the sort who tend to have labels ascribed to them such as 'socially excluded', 'disconnected' or 'hard to reach' – but they are not any of those things in reality. The research has generated findings and reached conclusions that challenge much of the current UK policy orthodoxy about youth unemployment, 'the NEET problem', so-called 'cultures of worklessness', the alleged need to 'raise aspirations' and so on and so on.

On the basis of this work we produced an impact case study for the 2014 REF. We claimed to have had various sorts of impact on a range of people and organisations. How convincing are these claims for impact? There is room for doubt.

One example concerns a North East England social regeneration quango. This is a body with whom we worked quite closely during the research, who sat on conference panels with us, who knew our research and who, we thought, had at least 'got' some of our key messages (for instance, about the desperate need to create more and better quality opportunities for young adults so as to combat economic marginalisation and poverty). Yet, very soon after we wrote our impact case study, this quango launched a new multi-million-pound initiative to 'tackle social exclusion' and youth unemployment. This programme seemed oblivious to our research and, in fact, was based on claims and assumptions – for instance, that youth unemployment is a fault of young people's 'low aspirations' and lack of 'work readiness' - that ran directly counter to our findings and conclusions.

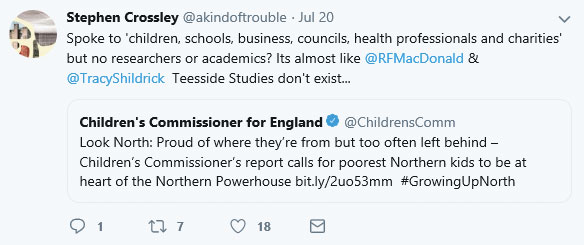

A second example was drawn to my attention by Dr Steve Crossley of Northumbria University, tweeting as @akindoftrouble

The tweet relates to a report produced by the Children’s Commissioner for England in summer 2018, entitled 'Growing Up North: a generation of children await the powerhouse promise'.

The introduction to the report explains that:

'Growing Up North' is the culmination of twelve months of research, analysis and conversations with children, schools, business, councils, health professionals and charities. It is designed to increase understanding of children’s attitudes, aspirations and expectations, look at the progression of children from early years to early adulthood and assess the opportunities provided by the Northern Powerhouse to children growing up in the North (my emphasis)

There is not the space here to engage in any detail with the report’s various findings and recommendations. There are undoubtedly some interesting points of view and conclusions that many people might agree with. My concern comes before that – in exercises like this, who is consulted and who is ignored? As Steve Crossley hints, no academic researchers appear to have been invited to report to the consultation and no extant research from the North East, on the vital questions the report poses for itself, appears to have been examined and used.

Our own Teesside Studies asked questions of direct and obvious relevance – and we talked with children and young people about their attitudes, aspirations, expectations and transitions to adulthood in detail, in the round and over the long-term. We believe we would have had useful things to contribute. Not least we would have strongly questioned the underlying but unquestioned assumption of the report that the deep-set problems facing young adults in the North East (e.g. high levels of poverty, underemployment, inequality, long-term economic dispossession and deindustrialisation, etc.) might be fixed with a focus on 'underperforming schools' and higher levels of educational attainment. High rates of graduate underemployment in the North East alone betray the problem with this line of thinking.

Why were we and other researchers not asked to participate?

We can only speculate on the answer in this case; it is possible that critical perspectives like our own might jar with the policy orthodoxy. But we can ask ...

given the clamouring insistence on researchers to make their work of use to policy makers and influencers, might we not similarly insist that those with some power to change things actually use the research that we do?