Music for all?

Jayne Price

HudCRES

In January, the School Standards Minister Nick Gibb announced that “in order to ensure all pupils are able to enjoy high quality lessons, schools are to receive a new model music curriculum created by an independent panel of experts”. The announcement was met with some consternation from the music education community. Thirty Initial Teacher Education colleagues signed an open letter to the Department for Education (DfE) which questioned the make up the expert panel in which teachers with substantive classroom music teaching experience are significantly under-represented in favour of colleagues from music hubs, music conservatoires, the Arts Council, the Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music (ABRSM) (who provide graded instrumental music examinations) and professional musicians. The decision to ignore the DfE’s previously appointed Expert Subject Advisory Group for music is somewhat baffling, given that this group includes pedagogic experts from higher education and music teachers from primary, secondary and special schools who do have considerable experience of teaching, assessment and curriculum development.

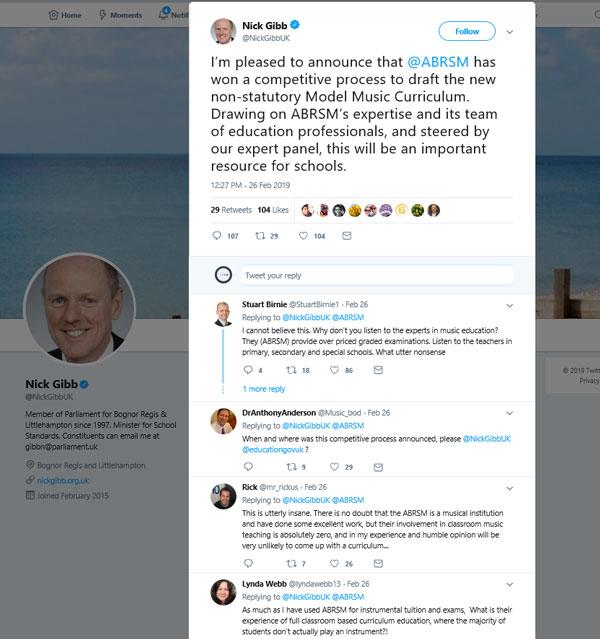

Later, Mr Gibb announced that the ABRSM had won a ‘competitive’ process to draft the new model music curriculum. This received an incredulous response from music teachers on Twitter and a hundred teachers signed an open letter to the DfE expressing grave concern about the lack of representation of classroom music teachers on the expert panel, the lack of transparency in the awarding of the contract to the ABRSM - an exam board with no experience in the teaching of curriculum music, and the lack of time for appropriate and meaningful consultation across the sector.

For me, it is the musical hegemony that underpins the choice of the members of the ‘expert panel’ and the award of the curriculum development contract to the ABRSM that I take most issue with. The minister makes no secret of his belief that music of the Western classical tradition is ‘more rigorous’, ‘high quality’, simply better than any other form of music. Writing in The Times (11/2/19), he explains:

As schools minister, I worried that some children’s music diet may be restricted to their own Spotify playlists, so we began working with Classic FM, the Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music and Decca to produce the Classical 100 – quality recordings of some of the most important pieces in the classical music canon

A hastily arranged consultation from the expert panel with some of my colleagues revealed the panel’s aim to develop a model curriculum in which pupils gain an appreciation of the history of music, leave primary school being able to read music, have opportunities to sing and play an instrument and have the confidence to progress to GCSE. Again Mr Gibb’s personal musical values are at play:

Too few pupils are benefiting from a sufficiently rigorous approach. I want every child to leave primary school being able to read music, understanding sharps and flats, to have an understanding of the history of music, as well as having had the opportunity to sing and play a musical instrument.” (Gibb 2019)

Focusing on the appreciation of (classical) music and reading music as if they are the most important skills and placing these at the centre of the model curriculum, exposes a fundamental ignorance of the nature of musical understanding and the pedagogies which develop this through engaging pupils as musicians, supporting and challenging them to make musical decisions and to create and perform music that ultimately engages and affects an audience. Those of us who do read music learnt alongside learning to play an instrument, and the aural skills required to play a part sensitively with others, to respond musically and to communicate with an audience are much more fundamental to my musicianship.

The placing of Western Art music at the centre of the music curriculum and the associated emphasis on musical literacy and theoretical knowledge develops a deficit model in which music educators are responsible for enlightening pupils to a particular music education agenda. As Spruce (2015) argues, this implicitly devalues music that lies outside this tradition and those whose musical voices do not articulate these ‘legitimised’ messages are likely to disengage from school music and the formal music curriculum.

The proposed model curriculum is a poor response to the current crisis in music education in which engagement and participation in music outside of the compulsory curriculum is at an all-time low. If we are to develop a curriculum which provides rich musical opportunities for all pupils, which Mr Gibb seems committed to, we need to start by nurturing and valuing all musical abilities and all musical traditions.