Teachers as poets, teaching as poetry, and lessons as poems

Judith Kidder

HudCRES

Would it make a difference to how we learn to teach and think about teaching if we thought of teachers as poets, learning as poetry and lessons as poems? What do poets say about writing poems and how might this have resonances for what teachers and teacher educators say about teaching lessons?

I am coming to the end of my career as a teacher and teacher educator, so this post is likely to be my first and last and, like a message in a bottle, I will be casting it out to sea without ever finding out where or whether it washes up. Out of all the work I have done as a teacher, I decided to share my thinking about how teachers might be seen as poets.

Poems, like teaching, learning and lessons, can be complex, surprising, powerful, intricate, transformative, making the implicit explicit; they can also be complicated, difficult, paradoxical, making the explicit implicit.

I chose this subject for several reasons:

- Firstly, because reductionist, technicist and competence based tendencies in teaching and learning seem to minimise considerations of the artistry of teaching:

The missing ingredient pertains to the crafting of action, to the rhetorical features of language, to the skill displayed in guiding interactions, to the selection of an apt example. In short what is missing is artistry… Artistry requires sensibility, imagination, technique and the ability to make judgements about the feel and significance of the particular. (Eisner 2002:382).

- Secondly, out of an interest in the way forms of writing may, or may not, constrain both thinking and what can be said. ‘Permission to use new tools and new forms of representation enables us to look for different things and to ask new questions’ (Eisner 2002 :380).

- Thirdly because metaphor can be seen as fundamental to the structuring of conceptual knowledge (Lakoff and Johnson, 1980).

Strong links between poetry and learning already exist: pre- writing cultures made use of rhythmic and repetitious forms, in order to aid memorisation and for the oral transmission of traditions and stories. That this correlation is already embedded in the culture gives ‘teacher as poet’ rich potential for understanding and exploring connections.

Poetry as inquiry

Drawing on the work of Donald Schön, and the ways in which metaphors allow new and different perceptions and explanations to be generated, I developed an activity in which trainee teachers towards the end of their initial training were asked to respond with words, phrases and sentences to stimulus phrases about teaching and being a teacher such as ‘I used to think that/I’ve learnt that’ and then to work collaboratively in small groups to braid together and re-shape the words collectively. Trainees also responded to the question what might teaching and learning look like if teachers were seen as poets and lessons were poems?

Extracts of texts by literary poets on the subject of poetry were introduced to consider what some poets said about writing poetry and trainees were asked to collaborate to weave the words of poets with their own to form further poems about being a teacher and about teaching and learning.

According to Gold (2012: 756), poetry can be viewed as a form of qualitative phenomenological inquiry—a way of making sense of lived experience, a conversation with one’s environment and a way to give voice to that which is not easy to articulate; poetry in professional education can provide opportunities to consider multiple perspectives and ways of viewing the world in different ways, developing ‘higher level’ thinking skills; the explicit use of generative metaphor can make explicit and facilitate understanding of ‘the tacit deep metaphors that underlie teachers’ discourse, as well as the frame of restructuring their role as teachers’ (Vadeboncoeur and Torres, 2003:88).

Poetry as an alternative form of writing

I also wanted to explore the use poetry as an alternative way of writing from traditional educational or academic discourses with the intention of facilitating the exploration of different conventions, constraints and expectations and how these might elicit different kinds thinking and different kinds of responses. Academic writing, for example in essays, tends to be a formal means for trainee teachers to make their knowledge explicit. Opinions expressed are part of a wider analytic approach which uses evidence from other reputably researched and published sources to provide an overview of particular arguments and to make critically analytic judgements about them.

Teaching, though potentially scholarly, is arguably a different type of activity. It can consist, for example in lectures, of the personal presentation of academic writing in the presence of learners in order to share with novices what the expert already knows. Current thinking about teaching and learning emphasises more interactive strategies which involve and engage learners in their learning. This may vary from, for example, the use of activities and discussions which appear to involve the learners and lead them to what the teacher wants learners to be able to know, do or understand, to less prescribed approaches in which learners and teachers co-construct knowledge together through facilitation with the purpose of enabling teachers and learners to think about, problem solve, reflect on and wonder about topics, issues and experiences to create meaning and new knowledge.

Are teachers scholars (researchers?), artists or both?

Robert Frost, talking about poets, might also be seen to provide an alternative way of knowing which might have resonances for both teachers and writers who fall somewhere between the two:

Scholars and artists thrown together are often annoyed at the puzzle of where they differ. Both work from knowledge; but I suspect they differ most importantly in the ways their knowledge is come by. Scholars get theirs with conscientious thoroughness along projected lines of logic; poets theirs cavalierly and as it happens in and out of books. They stick to nothing deliberately, but let what will stick to them like burrs when they walk in the fields (Robert Frost, 1949).

A requirement to submit written reflections for assessment purposes can present tensions in the attempt to reconcile very different approaches to writing: the self almost inevitably has a greater presence when writing about personal experiences; and, because writing about experience has the potential of being personal, exploratory, collaborative, fragmentary and uncertain, it might not be seen as scholarly in a traditional sense.

A pitfall of requiring particular sorts of written reflection from trainee teachers risks what Leitch and Day 2000:188 refer to as ‘a well-rehearsed, but limited approach to reflection on feelings ie intellectualising which is usually self-serving, justificatory and thereby defeats the goals of arriving at new insights or clear decision-making or problem finding/solving’. However, teachers should be able to think about, experience, develop, explore and play with other ways of knowing, and teacher educators, as modellers of different kinds of learning practices, should be able to share different ways of facilitating thinking and writing about teaching and learning and what it is to be a teacher as ‘…not only does knowledge come in different forms, the forms of its creation differ’ Eisner 2008:5.

Poetry and teaching as creative activity

In terms of the classroom activity, the discussion between trainees in order to produce the poems was as significant as the created poem itself. Of specific importance, however, was the review and plenary session which focussed on insights from process, form and content. Trainees were asked to evaluate the session in terms of how it might impact on both their practice and their writing.

Some stereotypical correspondences between poetry and teaching emerged, for example, a romantic notion of poet was more favourable than that of technician or operative. There were also considerations of the ways in which lessons, and indeed essay writing, like poems, might be crafted, worked on and developed.

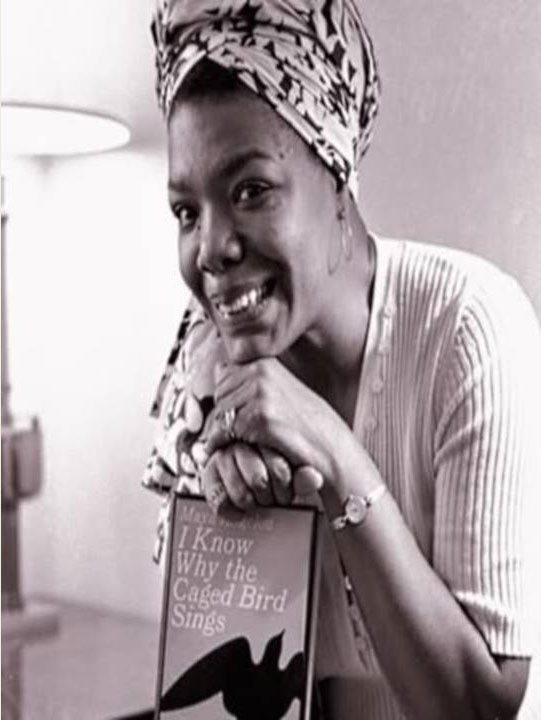

My mission in life is not merely to survive, but to thrive; and to do so with some passion, some compassion, some humour, and some style.

Maya Angelou

Auden, a poet discussing poetry, considered in the context of teaching however, promoted discussions which highlight the agency of the teacher in creating a lesson, the potential difficulties for teachers of both a focus on craft and in knowing in advance ‘what works’. Some new teachers, despite their careful planning and inclusion of check-listed requirements were similarly unable to envisage their lesson until after they had taught it. Teachers with more practice based experience considered the implications of departing from ‘specifications’ and the ways in which they allowed lessons to develop with the learners, but also expressed discomfiture at working without any ‘specifications’ at all.

A poem does not compose itself in the poet’s mind as a child grows in its mother’s womb; some degree of conscious participation by the poet is necessary, some element of craft is always present. On the other hand, the writing of poetry is not, like carpentry, simply a craft; a carpenter can decide to build a table according to certain specifications and knows before he begins that the result will be exactly what he intended, but no poet can know what his poem is going to be like until he has written it ( WH Auden)

My own evaluation of the activity was that from expression in a poetic form, unconstrained by the conventions of a narrative or discursive written format, a succinctness and compression of language emerged which allowed different kinds of responses to develop, mediated by the form. The idea of ‘the Poet Teacher’ had some resonance, albeit not without reservation, for some teachers.