Dr Ron Thompson

Principal Research Fellow in Education

...evaluates GCSE reform, attainment gaps and performance of ‘poor children’ and asks are we going Back to the Future?

Headlines announcing that the gap in educational achievement between rich and poor has widened are always likely to grab attention, particularly around the recent election campaign. Following evidence earlier this year that the least-advantaged children in England were 18 months behind their richer peers, a recent report (Burgess and Thomson 2019 – Making the Grade, published by the Sutton Trust and written by Simon Burgess of Bristol University and Dave Thomson of the private research organisation FFT) on the social impact of new-style GCSEs received widespread media coverage. The report analyses the way in which attainment gaps between different groups of pupils have changed since the GCSE curriculum reforms, initiated by Michael Gove, Secretary of State for Education between 2010 and 2014. It shows that these reforms have been associated with a small, but statistically significant, increase in the attainment gap between disadvantaged and non-disadvantaged pupils. But what exactly does this finding mean? Who are the groups of pupils it refers to, what kind of changes have occurred, and why might they have been produced by the Gove reforms? Perhaps more importantly, what should be the future direction of reform? To answer these questions, we need first to look at the origin and development of GCSEs themselves.

Forty years ago, the system of qualifications for 16-year-olds in England was socially and academically divisive, still reflecting the tripartite hierarchy of grammar, technical and secondary modern schools established following the 1944 Education Act, but largely dismantled by the comprehensive reforms of the 1960s and 1970s. Students deemed to be academically able took the General Certificate in Education (GCE) at Ordinary Level – the ‘O’ level exam – whilst some of those considered less able took the Certificate of Secondary Education (CSE). In its early days, GCE ‘O’ level was graded from 1 to 9, with 1 being the highest grade and 6 being the pass grade. Later, this was rationalised into broader alphabetic grades, with A-C being passes. The CSE exam was graded from 1-5, with grade 1 being nominally equivalent to a grade C pass at ‘O’ level. The median level of achievement for all children was considered to be CSE grade 4, reflecting the fact that many children sat no external examinations at all. In making sense of this system, it needs to be remembered that the school-leaving age had only been raised to 16, from 15, in 1974, so that even taking CSE entailed students remaining in school for an additional year.

It is not surprising that such a system of examinations caused widespread dissatisfaction, and even anger. Some experimentation with alternative curricula took place, and the Schools Council 16+ examination used in some areas provided a step towards a single system. However, the White Paper, Secondary School Examinations - A single system at 16 plus, introduced in 1978 by the Labour Government led by James Callaghan, was temporarily shelved by the Thatcher Government and the new, unified General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE) courses did not begin until 1986, with the first examinations being taken in 1988. These new examinations were a fairly radical departure from the previous system. Not only did they introduce a single qualification for all pupils, they were founded on the principle that students should be enabled to ‘show what they know and can do, rather than what they do not know and cannot do’. To reconcile these aims, and to found the examinations on a broader range of knowledge and skills, innovations such as tiered examinations and coursework became a part of GCSE courses, and the expectation of much higher pass marks was a significant part of the official rhetoric as teachers were trained for the new courses. Later criticisms of ‘dumbing down’, and the eventual modularisation of many GCSEs, need to be seen in the light of these aspirations for a more inclusive 16+ curriculum, one that would reduce inequalities by drawing virtually all 16-year-olds into a qualification system built around positive achievement rather than scraping through an examination designed for the most academically able.

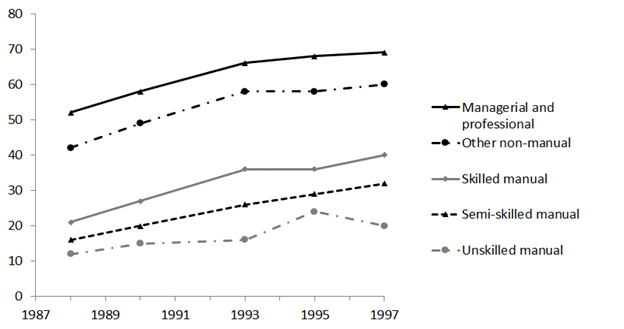

In some ways, GCSE was a resounding success. It swept away the anachronistic divisions of the earlier system, brought fresh impetus to teaching and learning, and was able to cope with the raised expectations brought about by the massive expansion of 16-19 and higher education seen in recent decades. However, it was also dogged by criticism – that it was a poor preparation for further academic study, that standards were compromised by coursework and tiering, and that ever-increasing pass rates demonstrated that the exams were too easy for many pupils. Nor was GCSE successful in reducing social background inequalities. As Figure 1 (below) shows, in the ten years after its introduction the proportion of students achieving 5+ passes at A-C increased markedly for all social classes. However, the attainment gaps between these classes remained almost constant.

More recently, this pattern has continued, although data on attainment by social class has become more difficult to obtain, whilst eligibility for free school meals (FSM) has become the standard measure of disadvantage. However, as Sonia Ilie (2017) and her colleagues have shown, FSM-eligibility is a rather blunt instrument for measuring disadvantage, particularly when based on eligibility at any time within an extended period. The definition of disadvantage used by Burgess and Thomson is of this type, including all pupils who were “eligible for free school meals at any point in the six years up to and including the year in which they reached the end of Key Stage 4”. Other, more sophisticated, measures of socioeconomic status have been used, which rather than a dichotomous eligibility criterion construct a continuous scale drawing together both individual factors such as FSM-eligibility and neighbourhood measures of advantage/disadvantage. However, when used in other research, these measures have not differed greatly in their implications from the FSM-measure, giving some confidence in the analysis of Burgess and Thomson.

Turning now to the report itself, Burgess and Thomson begin by outlining some of the key changes introduced by Mr Gove. These include:

- More challenging content, whilst remaining ‘accessible’ to all pupils;

- A terminal rather than modular structure, replacing exams at the end of each module with a final examination – rather like the old ‘O’ level;

- An end to coursework and non-written assessments, except where essential (as with languages) – again, just like ‘O’ levels;

- Replacing the alphabetical grades (A*, A, B, …, G) with numerical grades which reversed the order used in ‘O’ levels (9, 8, …, 1). Thus grade 1 is the lowest grade, and there is an opportunity to introduce grades beyond 9 in the future;

- Splitting the two highest grades A-A* into three grades, 7-9;

- Eliminating tiering in all but a few subjects (maths, for example).

Although a 2019 GCSE paper still looks very different to the ‘O’ levels I took in 1970, it is fair to say that these changes are aimed at reversing the measures introduced to make GCSEs more inclusive than their predecessors. In particular, the principle of students demonstrating what they know and can do has been virtually abandoned: for example, the AQA grade boundaries for 2019 show that to achieve a grade 4 in mathematics (equivalent to a grade C pass in the previous system), candidates needed to score only 18 per cent. Such a student knows and can do very little in relation to the exam paper in front of them, whatever they may have learned in the course as a whole.

The impact of the reforms on the distribution of grades has so far been limited, at least partly because grade boundaries have been manipulated to keep the proportion of candidates achieving grades 7-9 and 4-6 in line with the proportion formerly achieving grades A-A* and B-C. Thus 10 per cent of disadvantaged pupils and 24 per cent of non-disadvantaged pupils achieved grades 7-9, the same proportions as formerly achieved A-A*. There was a small increase in the proportions achieving grades 4-6 compared with grades B-C, from 42 to 44 per cent for disadvantaged pupils, and from 50 to 52 per cent for non-disadvantaged pupils.

Perhaps the most dramatic impact of the reforms has been the consequence of splitting the highest grades, so that grade 9 is more difficult to obtain than was grade A* under the previous system. Pre-reform, 2 per cent of disadvantaged pupils achieved an A*, compared with 8 per cent of non-disadvantaged pupils. Post-reform, these figures are 1 per cent and 5 per cent respectively, and Burgess and Thomson show that, after allowing for other pupil characteristics and school effects, non-disadvantaged pupils are 3.37 times more likely to achieve a grade 9 than disadvantaged pupils. This compares with a ratio of 3.26 for those achieving grade A*, a small but statistically significant increase. It also needs to be remembered that the dichotomous FSM6 measure of disadvantage is relatively crude, telling us nothing about differences within the non-disadvantaged group. These differences are likely to be large, given that ‘non-disadvantaged’ includes the wealthiest families alongside those only just above the threshold of eligibility for free school meals.

Burgess and Thomson highlight two factors that may be involved in these new attainment gaps. First, even without any change in the behaviour of disadvantaged and non-disadvantaged groups, splitting the highest grade would be expected to increase differentials at the new top grade, simply because the grade boundary is higher. Assuming something like a normal distribution, a difference in average performance between the two groups will result in many disadvantaged pupils ‘missing the bus’ as the boundary increases. Second, the reforms may lead to changes in behaviour, or intensify the impact of existing socioeconomic differences: more advantaged families may spend more on private tuition to compensate for a more challenging curriculum; the ability of more educated parents to help their children may become more significant; overcrowded, poor housing conditions may reduce the ability of disadvantaged children to respond to the changes by working harder; or these children may simply be discouraged by a moving goalpost. Because examining boards have sought to retain comparability at certain key thresholds – A-A* and C – the impact of these two kinds of effect has, for the moment at least, been minimised, accounting for the relatively small differences revealed by Burgess and Thomson. However, if the academic and political focus shifts, the impact of the reforms may well increase.

Political rhetoric over standards and ‘excellence’ eventually has social effects, and it is possible to foresee how the Gove reforms may facilitate more dramatic changes in attainment gaps. Already, the focus is beginning to shift from grade 4 – considered a ‘standard pass’ – to grade 5, now considered a ‘strong pass’. As the above arguments show, attainment gaps at grade 5 are more likely to increase in future than those at grade 4, so that if strong passes in key subjects become the new benchmark there will inevitably be an impact on GCSE achievement gaps and ultimately on social inequalities in HE entry and on employment. Unless the newly-created attainment gaps highlighted by Burgess and Thomson can somehow be narrowed, fetishising the new grade 9 will also affect entry to more elite sectors: the Russell Group universities, the traditional professions and ‘blue chip’ companies. This work needs to begin much earlier than at GCSE: if a large factor in the new attainment gaps is due to socially-generated differences in performance, pre-school and primary school education become a critical arena for change. However, as I have argued in my recent book, Education Inequality and Social Class, educational inequalities cannot be separated from broader inequalities in society, particularly those of income and wealth. A holistic approach is needed, in which progressive rather than regressive educational policies work together with broader social and economic policy to both reduce inequalities and the opportunities for more advantaged families to exploit their advantage. If the newly-elected Prime Minister Boris Johnson is serious about his pledge not to forget those people in formerly Labour constituencies who have ‘lent’ him their vote, this is one of the challenges he will need to face.

Education

Browse all our blogs related to Education.