Tricorn hats, bells, breeches: town criers & ‘invented tradition’

This summer, thanks to a grant from the Janet Arnold Award, I will be researching why town criers wear such outlandish costumes. This might seem an odd choice for a research topic but I hope by the end of the blog you will share my enthusiasm. I first became interested in the role of town criers during my doctoral research on oratory and political mobilisation in the Chartist period. The 1840s were a period of dynamic social and political change when the key reform bodies of the period (anti-slavery, Chartism, temperance, free trade) employed travelling lecturers to host meetings in market squares and lecture halls across the country. These meetings were an important mechanism for circulating information and propaganda to audiences of working people. On arrival in a strange town the first thing an itinerant lecturer did was to employ the services of the local town crier to call a meeting and raise an audience. Despite their important role in disseminating news I was surprised to find no historical writing on town criers aside from hagiographical accounts of individual criers. Once my PhD was completed I worked as a research assistant on an oral history project at the University of Huddersfield on Yeoman Warders – or Beefeaters as they are more popularly known. Interviewing Beefeaters and learning about their archaic costumes led me towards a new interest in heritage and tradition. It also made me think more about the role of dress in evoking the past. Town criers were thus an attractive proposition for a research topic as no-one has written about them and they combine my interest in oratory (the town crier belongs to a pre-literate culture of oral announcements) and the reinvention of tradition.

So what do we know about town criers. For centuries English town criers and bellmen provided news and urban spectacle. Their distinctive call of ‘Hear Ye, Hear Ye’ vied with the cries of street sellers contributing to the cacophony of the urban soundscape. When announcing matters of public interest, the crier’s noisy bell, his stentorian voice and extravagantly styled dress was calculated to capture attention and keep it. In many towns and cities town criers were part of civic government and the office gave them a small stipend, a costume and a modicum of social standing. In other places the role was less formal. Here freelance criers or bellmen would call messages for anyone willing to pay a small fee. Rising literacy rates and changing media meant that by the end of the century town criers were largely obsolete. Intriguingly, as the town crier became increasingly irrelevant, he became a romanticised symbol of a disappearing, traditional, English life. Indeed after they ceased to serve a practical function, they were retained in certain towns in a conscious attempt to retain ancient town traditions.

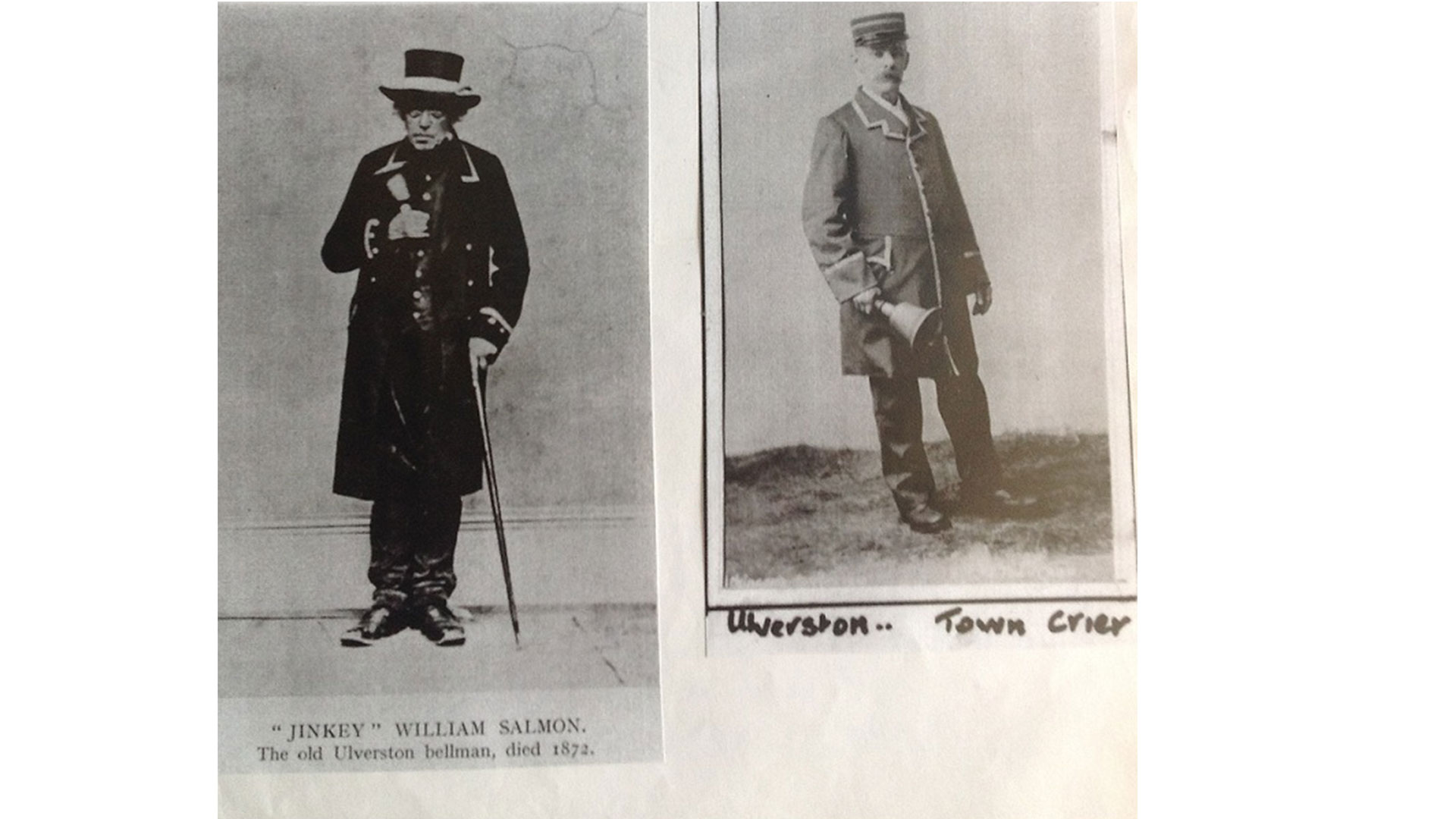

When ask to describe a town crier most people would mention the tricorn hat, bell, breeches and bright coloured cloth. Today town criers are most commonly attired in a dress that harks back to the Georgian period. Why is this so? A preliminary survey of nineteenth century town criers shows that while some did wear elaborate livery (particularly in historic towns with civic ambition) others wore peaked or bowler hats and were clad in nondescript clothing, distinguished as criers only by their bell. Of course this disparity in costume can partly be explained by rank, a freelance crier who eeked out a few pence crying messages for neighbours and visitors was at the opposite end of the social spectrum from officially appointed town criers employed by more illustrious city corporations. There were also regional differences in dress. In Scotland, for example, town criers typically carried a drum not a bell.

By the 1930s town crier competitions were regularly held, often sponsored by national newspapers, such as the News of the World. (Here you can see footage of an event held in Lyme Regis in 1939 http://www.britishpathe.com/video/oyez-oyez-oyez-town-criers-contest-at-lyme-regis) While criers were scored on the loudness and clarity of their cries they were also judge on their costume. As town criers became novelty heritage figures my hunch is that the costumes became more elaborate and pantomimesque. Individual criers invented costumes that they felt represented both their towns and their personal histories alongside the ancient traditions associated with the role. Key to this part of the research will be the private collection of material amassed by David Bullock, archivist of the Ancient Guild of Town Criers. Bullock sent a survey to all existing criers in the 1990s asking them to describe their costumes and send photographs. Although not all criers responded there is a sizeable amount of returns to be assessed. It appears that while some towns with an ‘official’ recognised town crier do specify the costume to be worn most places do not. This allows the town crier to indulge various whims and preferences, whether for ostrich feathers and Whitby jet or to adorning their costumes with regimental badges. The badges and regalia on Bullock’s costume documents his own personal work history in the navy and police.

My study will analyse the characteristic costume worn by town criers and consider how this not only attracted attention but also endowed the crier with authority and kudos. 1835 has been chosen as the start point as this is when the Royal Commission on Municipal Corporations produced a detailed survey of 285 towns in England. The detailed reports included information on town criers, their duties and pay and conditions. The livery worn by town criers was generally paid for by the corporation and sometimes the Royal Commission records how much it cost and what type of apparel was issued. I shall also examine how town criers were depicted in paintings, engravings and later photographs to determine how their dress changed over the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Such research will involve surveying the collections of picture libraries and repositories holding advertising and ephemera, including the Mary Evans Picture Library and the John Johnson Collection at Oxford. Paintings and sketches of local town criers are also found in local repositories such as Birmingham City Archives and Herefordshire Record Office.

By focusing on the costumes worn by town criers it is hoped that this project will shed light on the identities of those who take up the profession and how and why modern town criers present themselves as authentic bearers of a timeless tradition.

Dr Janette Martin

History at Huddersfield uses research-led teaching and a commitment to public engagement to ensure that what we do is both useful to society and beneficial to the employability of our students. We see our students as researchers – partners in the development of knowledge with academic staff, often through co-production of knowledge with community partners. For more information see http://www.hud.ac.uk/courses/full-time/undergraduate/history-ba-hons/ and http://www.hud.ac.uk/research/history/

You can email us at historyadmissions@hud.ac.uk