Bussing Out: an exploration into the impact of the Dispersal Policy on migrant c

The Dispersal Policy: Circular 7/65, 1965 proclaimed that:

About one-third of immigrant children is the maximum that is normally acceptable in a school if social strains are to be avoided and educational standards maintained. Local Education Authorities are advised to arrange for the dispersal of immigrant children over a greater number of schools in order to avoid undue concentration in any particular school (DES, The Education of Immigrants, Circular 7/65, London, HMSO, 1965, p. 4).

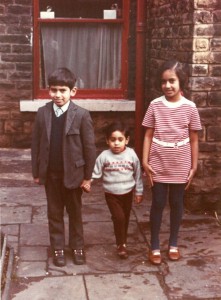

The children were put on buses from predominantly Black and Asian urban inner city areas to schools in outlying white districts. My PhD project, undertaken as part of the AHRC-funded Heritage Consortium explores the impact on the children and communities affected by the policy, which lasted into the mid-1970s. The principal methodology for my research is oral history: I’ve been listening to the interviews I’ve collected since March for feelings and stories that can provide an insight into identity formation. Taking a bus to school is part of the experience of education in an industrialised society, it is not necessarily exceptional in itself because education is outsourced from the immediate and extended family and provided by the state or private providers therefore requiring travel outside the community.

The cultural theorist Stuart Hall has argued that:

Identity is like a bus! Not because it takes you to a fixed destination, but because you can only get somewhere – anywhere – by climbing aboard. The whole of you can never be represented by the ticket you carry, but you still have to buy a ticket to get from here to there.[i]

This provides a useful way of thinking about the experience of bussing for children involved. Hall’s metaphor he says we can assume buses take you to a fixed destination. Mollie Summerville, a teacher in Bradford at the time, said “many of the children had no idea where the buses were taking them, they didn’t understand the relationship between where they lived and where the school was ”. Other interviewees have verified this. They only knew which bus to get on because were told to look for specific symbols, for instance a yellow ball or red diamond. They didn’t know where they were going, the name of the school or where in the city the school was in relation to their home. The children were shown the world through symbols. They could only “get somewhere – anywhere – by climbing aboard”. But where was it? Where were they being taken? They saw themselves, as being on the red diamond bus and on arrival at the school they found that the pupils with whom they were expected to integrate called it the “Paki bus”: leaving their neighbourhood they were red diamonds but on alighting they transmogrified into Pakis.

For bussed children the “fixed location” they were destined for became a conceptual space, a heterotopia of Englishness essentialised by Enid Blyton and Arthur Ransome. It consisted of Harvest Festivals, dancing round the Maypole, singing Christian hymns and reciting the Lords Prayer. One interviewee from a rural Pakistani Muslim background recalled being asked to bring tin cans for the harvest festival. These were meant to be items the family had in their kitchens and wouldn’t be missed. However, her mother never used food from cans and only cooked fresh food, so the mother had to go out and especially buy canned goods to take to school. The most common experience for all the bussed children was life lived on the periphery. They lived in the edges of the day, arriving late, leaving early and during the day circling the playground in groups of red diamonds.

Another Muslim Pakistani interviewee, Abdul remembers going carol singing with his mates round the houses of their neighbourhood and charging money: “we knew all the hyms cos we’d learn them at school. We used to just go round and get money for them”. He did the same with Guy Fawkes night, a smaller boy would be the Guy, wearing a duffel coat back to front and lie prone on the floor: “We’d get loads of money and spend it all on fireworks.[ii]”

The young boys were able to commodify their knowledge of English culture and turn a pretty profit. Interestingly as a grown man he does the same but on a corporate level. As a grown man, Abdul continues to use his acquired knowledge of Englishness on a corporate level. He runs a property management service for absentee landlords in Bradford and the company has a ‘posh-sounding’ English name, something like Harry Windsor Lettings and Property Management Services. This, Abdul feels, enables white people to trust the brand. It is an extremely successful business. As a child Abdul often bunked off school but loved reading, especially Enid Blyton…

Hall’s metaphor gives us a quick journey through the ways in which thinking about identity has changed since late modernity. After the Enlightenment identity was considered fixed, something innate that people were born with and never changed. Sociologists changed all that with symbolic interactionists suggesting that identity had an internal solid logic, it did change according to new influences at any given time. Hence the metaphor of the bus, the ticket changes according to the journey you’re on, or the part of the journey you’re on. The bus is the metaphor for stages in life and therefore signifies context and the ticket the identity label for the moment you’re in. For postmodernists identity is fractured and shifting; it is also performative, in that we act it out in the body: hence having to get on the bus in the first place, we all have to go somewhere and although we imagine a fixed location the route is discursive.

The experience of Abdul suggests exposure to what was considered a fixed notion of Englishness, nowadays often bemoaned by the media as a lost age. The bussed children learnt a way of perceiving the world through symbols resulting, then in the performance of those same symbols that make up an essentialised English culture and selling it for sweeties and fireworks. Or in other words a fragmented, shifting identity: shape-shifting to fit historical circumstances – including the dominance of market principles.

This blog has taken one journey on the bus to its culmination in the adult life of the bussed child. The PhD as a whole travels with a number of children, to consider identity formation in the context of the development of multi-ethnic Britain in the late twentieth and early twentieth centuries. What makes my research distinctive and different is that I explore particularly the performative acts of identity. My oral history interviews will provide the material for verbatim theatre, enabling the children’s testimonies to express their experiences and memories of riding the bus to unknown Englands and the sense they made of them.

You can listen to short clips from Shabina’s interviews on Soundcloud

[i] Hall, Stuart, ‘Fantasy, identity, politics’, in E.Carter, J.Donald, J.Squires (eds), Cultural Remix: 1995 : 65

History at Huddersfield utilises research-led teaching and a commitment to public engagement to ensure that what we do tries to be both useful to society and beneficial to the employability of our students. We see our students as researchers – partners in the development of knowledge with academic staff, often through co-production of knowledge with community partners. For more information see http://www.hud.ac.uk/courses/full-time/undergraduate/history-ba-hons/ and http://www.hud.ac.uk/research/history/

You can email us at historyadmissions@hud.ac.uk