Eco-Transformation: The Journey of Sugarcane Waste into Clean Cooking Fuel

Prof John Allport

Professor of Engineering, Department of Engineering and Technology

The School of Computing and Engineering

Dear readers,

I am entering a new realm today in starting this blog, but I think that this is the best way to show a fascinating project which is about to get under way. Most academic projects are only reported in specialist journals, but I think this is far too important and interesting to limit it to such a readership. The work that I am about to embark on embraces sustainability, environmental aspects, waste management and improving people’s health, so is relevant to a wide spectrum of the population in East Africa. This blog series will look at how we can take an environmental hazard, in the form of sugar cane waste, or bagasse, and transform that into something useful which is a benefit to the local Kenyan community, namely cooking fuel. We will follow the project through from conception to completion in stages as the development progresses, seeing how this will benefit the lives of the people involved.

This post looks at the beginning of the journey, describing how a chance encounter has led to a significant 2-year adventure linking the Global North and South in a venture to solve a problem which, although local in nature, is a step towards addressing an issue that affects us all, namely global warming.

So what is this big problem that we are trying to solve?

Sugar cane is one of the most widely grown crops in the world. To satisfy demand for the myriad of products made using sugar, from cakes and sweets to fuel for vehicles, we have inadvertently generated vast quantities of sugar cane waste, encompassing leaves, bagasse, and other plant matter. Sugar cane waste stands at the crossroads of sustainable practices and industrial innovation. Its disposal poses a significant challenge, contributing to environmental degradation and climate change. Yet, within these challenges lie opportunities for transformation.

The waste material is plentiful owing to the rate at which the sugar cane plant grows – up to 4 metres in a year, with 1 hectare producing around 93 tonnes of cane. (1 hectare equates to roughly 2.5 football fields) This 93 tonnes will produce around 12 tonnes of raw sugar, with the remaining 80+ tonnes being waste. The leaves are used as mulch for the next crop, however there is still a significant proportion of the cane ends up after the sugar extraction as waste, or “bagasse”.

Picture 1 Sugar cane bagasse

Picture 1 Sugar cane bagasse

Sugar cane bagasse

Bagasse can be used for a variety of purposes such as paper making, poultry litter and animal feed, however the greatest use is as fuel for the sugar mills themselves. Once dried, the bagasse can be burned to fuel the boilers used in the sugar making process. In sugarcane producing areas, bagasse is used as boiler fuel in many industries, for example brewing.

Picture 2 Bagasse being used as fuel in the sugar processing plant

Picture 2 Bagasse being used as fuel in the sugar processing plant

In many areas however, the amount of bagasse produced exceeds by far the requirements of the sugar mill for fuel. In these cases, the bagasse is dumped and left to rot.

Picture 3 Sugar cane bagasse being dumped

Picture 3 Sugar cane bagasse being dumped

In the example in this picture, 50 truckloads of bagasse per day are added to this dump from a single sugar mill. In the town where this is located, there are 4 sugar mills, each producing a similar amount of waste. This is extremely detrimental to the environment, as the decaying waste gives off methane, of which each tonne is equivalent to 29.8 tonnes of CO2. The leachate running off it from rainfall is highly acidic, and also pollutes the local waterways, which are the main source of drinking water in some of the more rural areas.

Picture 4 Water leaching from the bagasse after rainfall.

Picture 4 Water leaching from the bagasse after rainfall.

So how can we improve this situation?

As previously stated, there are other uses for bagasse, but there needs to be a demand for any product, as well as the initial investment to set up processing plants. One potential solution is to convert the bagasse into cooking fuel. Most people in rural Kenya and other parts of East Africa rely on charcoal stoves for cooking. These give off large quantities of carbon monoxide and particulate matter, both of which are detrimental to health. Much of the charcoal used is produced by illegal logging, which is also an environmental issue. Conversion of bagasse to cooking briquettes would seem to be an eminently sensible thing to do, and that is what Mr Forster Andanje of Carbon Footprint Ltd set out to do in North-Western Kenya. Forster developed a way to process the bagasse with no need to add any further binders or chemicals to hold it together in solid briquettes. These are ideal for cooking, burning longer and cleaner than the traditional charcoal that they replace. The main issue with the process is that the bagasse is very wet, around 50% moisture, when it comes out of the sugar processing, and it must be dried before it can be processed into cooking briquettes. This drying is done by spreading the bagasse out in the sun, which Kenya has plenty of. Unfortunately, given the tropical climate, it also has plenty of rain, which is why the sugar cane grows so well! This means that the drying bagasse must be covered up whenever it rains to prevent it from getting wet again.

Picture 5 Manual drying of the bagasse in the sun.

Picture 5 Manual drying of the bagasse in the sun.

This is a very labour intensive, manual process, but is key to the production of briquettes.

So what does this all have to do with an engineering research group in Huddersfield?

Although we are familiar with the problem of rain, we do not have much sugar cane in West Yorkshire! The answer lies in networking and collaboration, in this case through the World Association of Industrial and Technological Research Organisations (WAITRO). WAITRO is a global association of research and technology organizations and research universities that, amongst other things, facilitates collaboration between members. The University of Huddersfield is a WAITRO member, and I, along with some other staff from the University of Huddersfield, attended the WAITRO congress in South Africa in November 2022. At that congress, there was a poster session, where the process of making the fuel was the subject of a poster from Kibabii university in Bungoma, Kenya. Discussions of what was an unusual and interesting subject ensued over coffee, and as regularly happens in these cases, ideas started to be exchanged. One of the themes of the congress was collaboration, and things just grew from there.

Familiarity with video conferencing is one of the few good things to have come out of the Covid pandemic and that has made collaboration across continents much easier. The discussions continued remotely, and I then made a side trip from a visit to Uganda to visit the staff at Kibabii. One thing to note, distances in Africa are much greater than they look on a map, and times cannot be estimated from distance! From Kampala in Uganda to Kibabii is 260 km, however this took over 6 hours each way, not including the waits to cross the border between Uganda and Kenya. These were not helped by the fact that the taxi had to be officially exported from Uganda to Kenya in the morning, then re-imported to Uganda the same evening! Also, do not try crossing a border during a World Cup penalty shootout – everything stops whilst the Border Officials watch the match!!

The visit was well worthwhile, despite the inconveniences, as all parties got on well and agreed to work together to find potential funding to support a collaboration. It was also recognised at the highest level, with full VIP treatment and lunch with the Vice Chancellor.

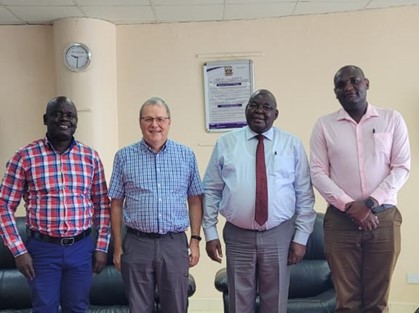

Picture 6 Meeting with the Vice Chancellor of Kibabii University

Picture 6 Meeting with the Vice Chancellor of Kibabii University

Following the visit, further discussions took place and we managed to find a suitable funding opportunity. This was a pilot funding call, based on the highly successful UK Knowledge Transfer Partnerships (KTPs). Four countries in Africa (Kenya, Nigeria, Ghana and South Africa) are wanting to set up their own KTP programmes and Innovate UK is assisting with that by funding some initial collaborations between African Universities and companies, in this case overseen and mentored by UK universities experienced in KTP projects. This fitted the bill perfectly and so we put forward a funding bid between the two universities and the company. After overcoming several unforeseen issues and several very late nights, the application was submitted and was ultimately successful.

This is where the story begins, and I will continue to tell it over the coming months as the project takes shape. We will consider the particular constraints that make a project like this in Africa so different to what we might normally expect in a UK university, such as how to convince people that a company in Africa exists, just because they do not have a website. They are lucky if they get power all day and internet access is a luxury in most cases! Please remember to like, share, and comment on each entry to foster engaging discussions, to spread awareness and drive positive change. Thank you for joining us on this transformative journey, and I look forward to sharing more experiences with you in my next blog post.